Side effects of chemotherapy

Most patients who receive chemotherapy have some degree of side effects. These may include:

Your care team will take steps to help manage side effects, including giving medicines to help control nausea, vomiting, and pain. Red light therapy may be used to prevent and treat mouth sores (oral mucositis). Your child may also need a nasogastric (NG) tube to give them food (nutrition).

Because of the increased risk of infection, your child will stay in their room on the transplant unit for their inpatient stay. All caregivers and visitors must follow strict guidelines for infection prevention.

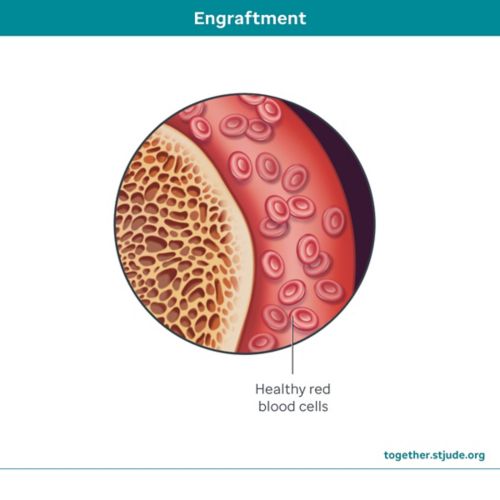

Low blood counts

The bone marrow transplant process may cause your child to have low blood counts. Blood transfusions may be needed to restore platelets and red blood cells.

Graft failure

There is a small chance that the new bone marrow from a matched family member will not work. The chance of this happening is higher with half-matched or matched unrelated donors. If this happens, your child will not be able to make white blood cells, red blood cells, or platelets, and the transplant would need to be done again.

Sometimes, the recipient’s own cells can grow back, which means that sickle cell disease could return.

Graft rejection

Graft rejection is a type of graft failure. Although uncommon, graft rejection happens when your child’s immune system recognizes the donor cells as being different and destroys them.

Patients who experience graft rejection can become quite ill. To prevent graft rejection, your child will get chemotherapy with or without radiation to destroy their immune system before the transplant happens. If your child experiences graft rejection, another transplant will be needed.

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

Graft versus host disease is when the immune cells of the donor (graft cells) sense that the cells of your child (host cells) are different and attack them. It can occur early or late in the process, and symptoms can range from mild to severe.

GVHD symptoms include:

- Rash

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Yellow skin and eyes

- Scaly skin

- Darkening of skin

- Hardening of skin texture

- Skin scarring/restriction of joints

- Dryness and sores in the mouth and esophagus

- Dry eyes and redness in the eyes

- Dryness of the vagina and other skin surfaces

- Drying and scarring of lungs

- Liver injury or liver failure

Your child will get immunosuppressant medicines to help prevent GVHD. It is very important that patients take all medicines exactly as prescribed.

Veno-occlusive disease (VOD)

Veno-occlusive disease (VOD) occurs when blood clots form in blood vessels in and around the liver. Bone marrow transplant, certain chemotherapy medicines, and frequent blood transfusions can increase the risk of VOD. VOD can cause increased bilirubin levels, an enlarged liver, water buildup in the body, or weight gain. If not treated, VOD can lead to organ failure and even death.

VOD is a serious condition. If your child develops VOD, they may need to be treated in the intensive care unit (ICU). VOD treatment often includes limiting fluids and treatment with the medicine defibrotide.

To help prevent VOD, your child may get the medicine ursodiol before hospital admission. Your care team will also monitor your child’s weight and fluid balance while they are in the hospital.

Social and emotional concerns

A bone marrow transplant is hard for both the patient and their family. Your child’s daily life will be different for a while since they will be away from home, school, friends, and family.

The family plays a big role in supporting your child during this time. On average, your child will stay in the hospital for 4–6 weeks. If you live far from the care center, you will need to stay nearby for at least 100 days or longer, depending on how well your child is doing after the transplant. Regular check-ins with a psychologist, social worker, and other care team members will help in navigating the transplant process.

Infertility

Some people who have bone marrow transplant may not be able to have children on their own. Chemotherapy can affect the ability to have children later in life. If your child is old enough, the care team may be able to collect their sperm or eggs before treatment so that they can be frozen and stored to use later if they choose. In some cases, ovarian or testicular tissue can be taken out and stored for future use.

Talk to your care team about your child’s risk of infertility and fertility preservation options that may be available.

Learn more about male and female fertility.